Grain & Folds

LISTENING

“Grain” describes the surface texture of a sound, which might be smooth, scintillating, or rough, and often reveals a type of facture and the material from which the sound body is constructed. Grain “leaves it signature on matter,” according to Schaeffer. (Dack, 2018, p. 42)

Sound originates with the interaction of surfaces but do sounds themselves have surfaces? ¶ 1

Sound surrounds, touching our surface with its succeeding waves of surface. Each peak and trough of the pressure wave is a new set of surfaces wrapping around, pouring in. What we might hear as surface in a sound is grain and texture, but this doesn’t live on the surface of sound, it is the sound. ¶ 2

Facture, according to Schaeffer via Dack, “is a quality perceived in a sound object that communicates how the sound might have been made…there is an implication of energy being applied to an object or medium” (Dack, 2018, p. 40). While mythology tells us that Schaeffer wanted to escape a sound’s source, this is an oversimplification. For Schaeffer, the way a sound was created was an integral part of the sound of a sound, and it needed to be considered in a far more sophisticated and analytical way. Actions and energy bring surfaces together, the combination creating sound. ¶ 3

* * *

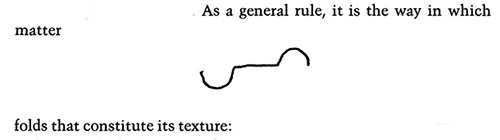

As a general rule, it is the way in which matter folds that constitute its texture: it is defined less by heterogenous and generally distinct parts than by the manner in which, by virtue of particular folds, these parts become inseparable. (Deleuze and Strauss, 1991, p. 245)

This is Deleuze’s notion of “the fold”, which is a reconfiguring of Leibniz’s proposal that texture is the passive resistance of matter (1991, p. 244)—surface friction. Deleuze’s theory of the fold offers many complexities that I don't have the time or space to enter into here. Rather, I am intrigued by a small diagram that interrupts the flow between the words matter and fold, despite matter being orphaned on its own line.

Deleuze and Strauss (1991, p. 245)

It is a mere squiggle—a concave semicircle (valley) that attaches to a roughly straight line (a plateau) that continues into a convex semicircle (a hillock). The curves above and below the midline are reminiscent of the graphic representation of a sine wave. After the interruption Deleuze continues: “Everything folds in its own way, the rope and the stick as a well as colours… and sounds…" (p. 245). I am tempted to interpret this as a beguilingly basic universal theory of everything—one that comes down to the texture and timbre of (the) matter. ¶ 4

In my fanciful re-interpretation it occurs to me that the ongoing iterative nature of theory—exemplified here by Schaeffer to Dack, or Leibniz to Deleuze, to me (and countless others)—is actually the application of different textures to old forms, a kind of reskinning. Is theorising actually re-upholstering? ¶ 5

Dack, J. (2018). Pierre Schaeffer and the (recorded) sound source. In J. A. Steintrager & R. Chow (Eds.), Sound objects (pp. 32–52). Duke University Press.

Deleuze, G. & Strauss, J. (1991). The fold. Yale French Studies, 80, 222–247. https://doi.org/doi:10.2307/2930269.