Reflection: Performing Listening

What is your relationship to listening?

I don’t really expect an answer to this opening gambit, but it offers an invitation to the participants to reflect on their listening habits—habits, in their very nature, being actions we undertake unconsciously. (See module (i): Listening to My Listening – A Listening Consciousness.) This invitation to the participants to become aware of their listening—to listen to their listening—plays out as the overall aim of the Listening Lingua interviews as a relational performance experience. I exchange this experience for their descriptions of the sounds.

Awareness of listening, for me, manifests as a heightened consciousness of my thoughts—an inner streaming monologue. I tap into this monologue when I need to write about sound. It also helps me understand what it is I’m making when I’m composing with sounds. I appreciate that this may not be the case with others, so the intention of the Listening Lingua interviews is to see how other people might move through this processing from listening to thought to language.

The articulation of thought in language is already a step removed, requiring a processing of thought into speech. The move to language can only ever be an incomplete record, a translation, which is something else again, not an exact equivalent. There is also the issue that not all thought is textual as it involves other modes, including the visual and conceptual (Vygostsky, 1986; Fernyhough, 2016). (1)Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES) is an experimental introspection testing process developed by Russell T. Hulburt, in which a participant is asked to log their thoughts when randomly prompted by a beeper. Hulburt’s results indicate that people vary greatly as to how much of their thinking takes verbal form. Studies of people in MRI machines indicated that 90% of people experienced inner speech but that it was dominant in only 17%. Based on DES studies outside the MRI testing, Hulburt concludes that 23% of beeped moments involved inner speech (Fernyhough, 2016, Loc 533). However, language remains the main tool we have to directly and immediately communicate this process to each other. There is drawing, movement—other art forms—but the first and everyday recourse is to speech. As noted in the introduction, there is a difference in the way we speak and write, but by invoking Jacques Derrida’s notion of arche-writing—the impulse towards language in which “writing” covers both speech and graphic inscription (Derrida, 1998, p. 55)—I suggest that the move towards the textual that occurs in speech is as equally rich and informative as writing, and more practical in terms of inviting immediate responses.

This essay focuses on the content and descriptive strategies expressed in the responses from the interview participants. I have a particular interest in how grammar is used within the descriptions. Given my research aim is to explore non-traditional methods of theorising, it may seem contradictory to use such a formal structure as grammar, but I am invoking grammar as a metaphorical tool, not a system of strict linguistic classification. I use it as a thought figure that assists in exploring the integral subject-object relations of sound and listening. This approach originates with Salomé Voegelin's proposition of sound as verb in Listening to Sound and Silence (2010):

Sound, when it is not heard as sublimated into the service of furnishing a visual reality, but listened to generatively, does not describe a place or object, nor it is a place or object, it is neither adjective nor noun. It is to be in motion to produce…listening to sound as verb invents places and things whose audience is their producer. In this appreciation of verb-ness the listener confirms the reciprocity of this active engagement and the trembling life of the world can be heard. (Voegelin, 2010, p. 14)

The Listening Lingua interviews are an exploration of this notion as to whether sound is a verb, not to prove conclusively, but to explore how grammar, viewed metaphorically, rather than systematically, plays out in our ways of understanding what we hear. (For more on my use of grammar within this research see theory analysis: chapter 1, “Seeking Words for the Heard”.

Codes and Modes

In processing the interviews I have settled on four categories of non-exclusive codes. (2)The following graphs indicate the number of instances of each code, divided by the total number of codings within the overall category. For example: number of cause/object responses divided by the total number of modality responses. From this a percentage is derived that allows comparisons to be made within and across codes and classifications.

1. MODALITY: the particular mode the participant taps into to describe the sounds and their listening.

CODES: aural, visual, conceptual-feeling, memory, imaginative-fantasy, physical-material.

2. ELEMENTS: the sonic qualities and elements that are described/focused on.

CODES: cause/object, material, textural/timbral, spatial, rhythmic, harmonic, energetics/kinetics/somatics, dynamics/densities/structures.

3. LITERARY STRATEGIES: approximate categorisations of the responses to individual sounds.

CODES: analysis, anecdote, description, fictional narrative, metaphor/simile/comparison.

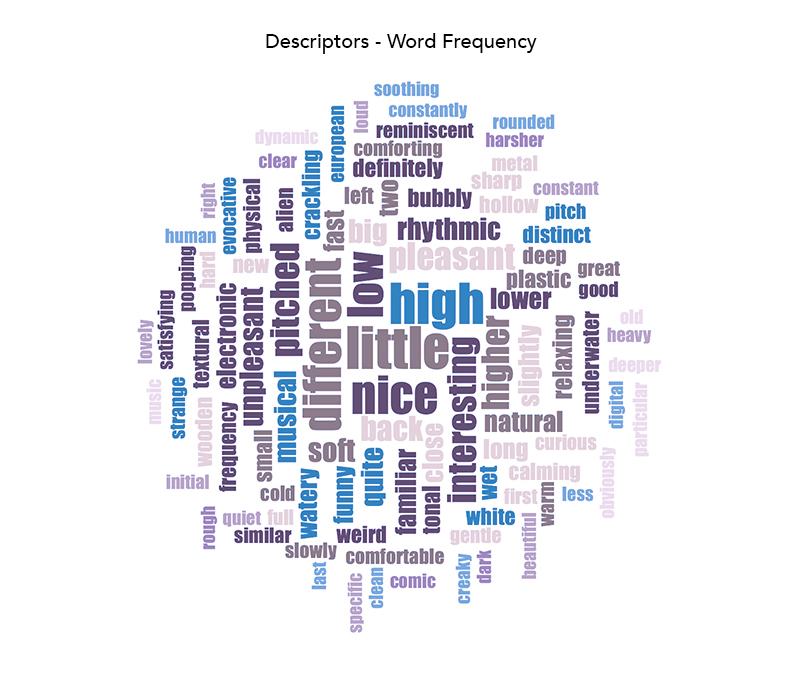

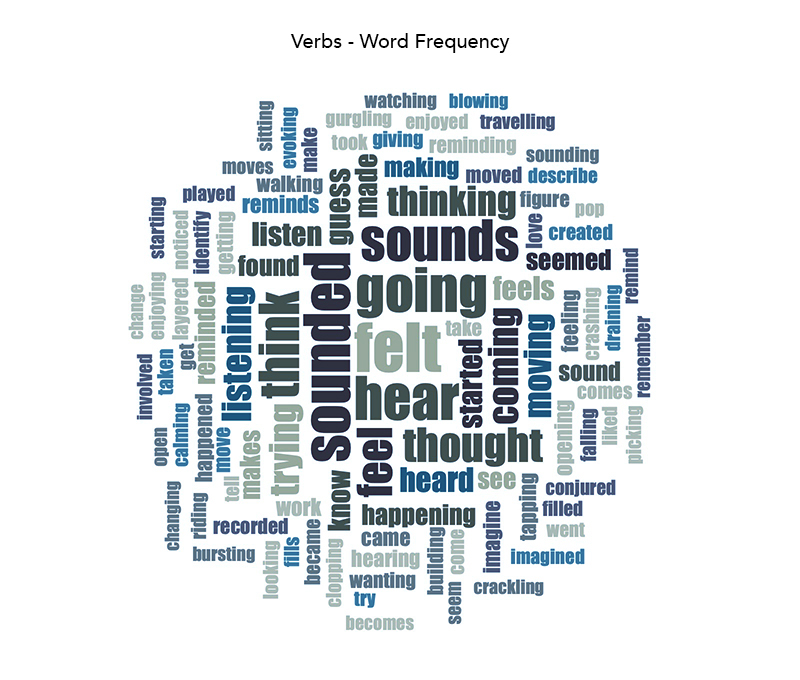

4. GRAMMAR: highlighting the basic forms used in descriptions.

CODES: nouns, descriptors (adjectives and adverbs), verbs, tense usage, pronouns, onomatopoeia.

All of the categories and codes (besides grammar) are non-exclusive, which allows for the identification of relations and alignments between them. For example, the cause/object element correlates to noun usage (beach, ocean, water, horses, hooves, bush, forest, door, hinges, pigeons, butterfly, computers); timbral and textural descriptions correlate to descriptor use (fizzy, harsh, popping, wooden, crackling, crinkly, dull, crittery, bubbly, fabric-ey, white noise-y); and spatial descriptions require prepositions and space related adverbs (towards, out, through, in, to, under, above). This may not be so surprising but it illustrates productive correlations between modes and grammar.

The use of pronouns provides insight into the subjective positioning of the interviewee within their listening experience. For example, a participant may use very few personal pronouns, focusing most descriptions around the third person it for the sound: “it sounds”, “it is”, “it’s like”. This creates descriptive responses that are analytical but also allow the sound to exist as an object-in-itself, an entity with some causal agency. (3) The sounds referenced in the responses are supplied afterwards. As there are multiple instances there are repetitions, however this allows for easy access and reader choice, which I believe justifies the redundancy.:

It was a very stretched out sort of sound. It's stretched and a little tortured and squeezed. Lizzy, Reduced Listening Sound 1

It sort of goes from slightly nerve scratchy through to comic. And it has a rhythm. Not a regular one. It's like it's descending. It's starting at a pitch and then descending… Helen, Reduced Listening Sound 1

Other participants reference themselves directly, “I feel/felt”, “I think/thought”, “I like/liked”, “I wanted”, illustrating a strong personal engagement. Some responses show a mix of third person and personal engagement with phrases like “it makes me feel” or “it reminds me”, emphasising the force the sound has upon them and the relationship that is fostered in the listening to sounds.

It's a sound that really speaks to me and I associate it with dance making… Martin, Reduced Listening Sound 3

Well, I love that. In terms of the synaesthetic thing, immediately I see little shapes… Penelope, Natural Listening Sound 4

I was particularly interested in how being directed towards different listening intentions might generate different levels of engagement. For example, when asked to focus on qualities within the Reduced Listening set (the qualities of the sound), would third person description and adjectival usage increase? While my coding does not stand up to quantitative rigor, and most participants move between these modes, one sound in particular, Sound 1 of Reduced Listening, does exhibit a strong propensity to be described in the third person, as the sound does have a very strong character. However, Sound 2 of Reduced Listening, perhaps even more obscure, sees an increase in first person as participants narrate their negotiation of this curiosity. The descriptions offered for both Reflexive Listening tracks, in which the participant is requested to reflect on their own listening experience, illustrate a personal perspective of journeying through the composition, even though Track 2 has considerable machinic content. While quantitatively inconclusive, it is still useful to be aware of these potential shifts when considering my larger aim of employing different strategies in my own writing.

Causes and Correlations

I was particularly intrigued as to how the type of the sounds themselves—for example those that hide their sources, such as electronic sounds, or those using specific manipulation or recording techniques—may encourage different modes of description, and identification of particular elements. This would illustrate Schaeffer’s phenomenological notion of the correlation between sounds and listening: “To each domain of objects, therefore, there is a corresponding type of ‘intentionality’” (Schaeffer in Chion, 1983, p. 26). Is it that sounds ask to be listened to in particular ways? For example, Sounds 1 and 2 of Natural Listening are recognisable, figurative sounds, which generate narrative descriptions of scenes and memories. Sound 3, although from a natural source, is both familiar and curious, with its energetic properties asking to be commented on, which introduces more abstract descriptions. The sounds and compositions made from synthesised sounds elicit qualitative descriptions, but also open up the territory for imaginative and fantastical figures and metaphors. The longer duration and layered nature of the Reflexive Listening compositions prompt responses that explore compositional structures and personal journeys of discovery within the interactions of sounds.

However, in parallel with the possibility that sounds suggest their modalities, qualities and elements, each person also has a particular set of preoccupations when they listen. Some seek texture and timbre. Others listen for spatial clues and need to know where they are located within the sound. Others respond to rhythm and dynamics, or memory and metaphor. And, of course, some touch on all these things. What becomes apparent is that even seemingly similar responses still have an imprint of the listener, evidence of that individual’s particular set of conceptual and emotional filters. This concurs with Grimshaw and Garner's argument for the importance of the “endosonic” component of sound—our brain-based memories and concepts—in the perception of sound (2015, see theory analysis: chapter 2, “Sounaurality: Ontologies of Sound and Listening”). Reinforcing the notion of the multiple subjectivities that listening generates is not a resignation into relativity, rather observing the many perspectives a sound may generate proves particularly beneficial for my sonic compositional practice, providing insight into how to create multifaceted compositions that activate a range of possible responses.

Poetic Particles Continuous

As previously mentioned, this research takes direct inspiration from Voegelin’s use of the verb as a thought figure for sound that is not a static object but a phenomenon actively becoming. She draws on Heidegger’s notion of “the Thing in its Dingheit, thinging”, so that “[t]he Thing as sound is a verb, the thing is what ‘things’ in its contingent production. To thing, it is to do a thing rather than be a Thing” (Voegelin, 2010, p. 19). With this purpose of doing, sound escapes the subject-predicate hierarchy and “becomes the noun as a thinging being” (p. 19). Embracing this noun-as-verb state, she frequently refers to the sound as a “world-creating predicate”, using this generative nature to explore notions of possible actual worlds (2014, p. 51; 2019, Loc 4387).

Similarly, Christoph Cox’s theory of sound as flux and flow draws on Deleuze’s proposal of “the ontology of the verb (events) as distinct from that of the noun (bodies) and adjective (qualities)” (Cox, 2018, p. 33). He cites Deleuze's proposal (after Nietzsche and Bergson) of “a pure becoming independent of a subject”. Deleuze suggests the infinitive of the verb best reflects this intention “bound to no subject or context. They simply describe powers of alteration in the world, powers of becoming that are variously instantiated” (Cox, p. 33–34). While Cox’s emphasis on the verb is useful, his preference for the infinitive renders it a theory that is hard to apply to the real world which requires conjugation for communication.

In the context of performance and the reception of music, Christopher Small suggests “the word ‘music’ shouldn't be a noun at all. It ought to be a verb—the verb ‘to music’” (1999, p. 12). “To music” or musicking, to which he adds an arcane “k”, incorporates all the participants—the composer, the performers, the audience, and even the support staff—who come together through the presentation of music. He argues that musicking enacts a set of relationships that are fundamental to human interaction. I suggest that at the core of this set of human musical relationships is an even more fundamental relationship, that of the sound (freed from anthropocentric constructs to allow for the broader vibrations of the world) and the reception of this via a “listener” (a thing that consciously receives the sound). Small’s choice of the verb to recast the notion of the sounding activity of music, and his choice of the present participle, is certainly informative.

With these ideas in mind, I have roamed through the interviews looking for interesting ways that verbs are deployed, with a particular interest in the present participle—the verb “verbing”. While I couldn’t offer an accurate quantitative breakdown, I could anecdotally say that the progressive or continuous tense, conjugated as the present participle, is a predominant form of usage. What is even more intriguing is that the present participle transformed to adjective and verbal noun is also very prevalent. The nature of an adjective or noun created from the present participle illustrates an active sense of description, an act of doing that is also occupying a state of attribute and/or object.

It sounded a lot like the soft crinkling of a thin plastic type of material. It had a popping kind of quality to it. But it also reminds me of when it’s just beginning to rain. Gabrielle, Natural Listening Sound 4

In this response the present participle crinkling is used as verbal noun (the crinkling of the plastic), popping is used as an attributive adjective (belonging to quality), while beginning is used in verb form to create the present continuous. This illustrates the flexibility of the present participle to be used across forms to emphasise the motion and action in the sound. In these usages we get a strong sense of the slipperiness of sound as it cannot be described by any simple grammatical attribute, its connection with action and movement bleeding into other grammatical forms. I won’t continue with the laborious grammatical breakdown; rather, in the following examples, I will discuss the effect that the present participle has across its usages.

I like the sound because it’s washing. It’s the ocean and the wind, the sloshing and crashing and bursting. Matte, Natural Listening Sound 1

In this description the sound is always in play, the present participles used as both verb and verbal noun. It illustrates how this sound is never settled, and the rhythm and repetition of the form match the rhythm and flow of the sound.

[Y]ou could never specify this percussive sound or that one, but [it] becomes a myriad of tiny hittings. Jim, Natural Listening Sound 1

It sounded as though there were—in water or a bath—things floating and tapping for a while. And that little popping—hardly popping—rattling sort of [makes noise ttt, ttt, ttt, ttt]…Then there was a whooshing, a bit more white noise-y sound. Things floating and bumping each other in a trough or a bath. Lizzy, Reduced Listening Sound 2

These responses articulate how a description of a sound as a stable state is inadequate, and how the appropriate mode is that which deals with the process and action. In these examples we can see how the verb is being pushed to perform as both noun and adjective.

I think of gurgling. Something going [cchhhh]. I can see it kind of bubbling. Maybe someone with a bucket filled with water and then [they’re] tapping the side with a stick, and then as they’re moving it some water emerges. A.S., Natural Listening Sound 3

It’s obviously water being moved and some sort of energy pumping it. There’s some sort of pipe or object that the water is moving through and it’s kind of gurgling with air and water, being forced in some way from one area to the next. Jim, Natural Listening Sound 3

In these descriptions the present participles indicate a distinct kind of agency or fabrication to the sound—either that of human agency, or elements within the “scene” coming together to make the sound.

It’s also interesting how the use of the present continuous plays out in the more imaginative and fictional responses.

It seems to be scanning, scanning for life forms, scanning frequencies. Matte, Reduced Listening Sound 4

I can see little characters squeezing out of a small space into somewhere bigger. Doing something naughty…And now they're going down the drain. Meghan, Reflexive Listening Track 1

I think particularly of train travel and looking out the window and perhaps travelling somewhere new and that being a pleasant, exciting experience…[but] it’s kind of good to be leaving, so extra potentiality. MP, Reflexive Listening Track 2

These responses evidence how the sound conjures an immediacy, a continuing presentness, even though what is described are imaginative, fictional and futuristic scenarios.

Relational Grammars

From these example we can see that the present participle allows the sense of action to be evoked not simply through verb form but also as verbal adjective and verbal noun. This suggests that to simply say that sound is a verb as Voegelin, Cox and Ihde propose is not nuanced enough. Other theorists have offered sonic ontologies that suggest different grammatical forms. Tim Ingold proposes that sound is not an object (noun) or an event (verb), but is “the medium of perception. It is what we hear in. Similarly, we do not see light but see in it” (2011, p. 39). This would implicate the preposition and adverb.

Within the interview responses positional prepositions and adverbs are prevalent in the sounds that offer strong spatiality.

That was interesting because I couldn’t work out where I was and if they were going around me or going past me. Susie, Natural Sound 2

That feels like being carried inside someone’s pocket. And you can't quite hear what's going on. Elle, Reduced Sound 2

With these samples the interviewee expresses a desire to locate themselves within the sound. The spatial descriptions illustrate how the sound is positioned in relation to the listener, but also how the listener positions themselves in relation to the sound.

It cleared something here and here [gestures around front of head]…And then at the end I could feel like something was acting—like a part of my brain was turning on that pink colour. A, Reflexive Listening Track 1

I experienced it all in the upper cortex here of my brain. This is my left side. So that was really interesting. And it happened within that quarter and the forefront of it. It all happened there for some reason, which is an unusual experience. Susannah, Reduced listening Sound 1

Positioning in relation to sound takes on a new dimension in these responses that draw on bodily and psychosomatic sensations. They indicate not just an immersion in the sound, but an internalisation of the sound itself.

These examples along with those of the previous section indicate the ways in which different grammatical forms allow for a focus on different aspects of sound. This is clearly illustrated when the verb morphs into adjective and noun through the present participle, so it seems too limiting to say that sound is represented by one grammatical form such as the verb. Sound is always in relation, a relation that is reflected by the relations that also exist in grammar. A sentence requires a complex interaction of forms—subject entangled with object or attribute through the action or becoming that is the verb. In this way grammar offers a powerful metaphorical and interpretive tool that can be used to explore the relations of sound and listening, as well as nuances of intention, and evaluative understanding of particular attributes.

Listening to Others’ Listening

I have struggled with the analysis of the responses to the Listening Lingua interviews because the pull towards making verifiable, quantitative assessments is strong. Presented with the raw interviews, a professional linguist may have come to different conclusions, however, I am operating as an artist pursuing a creative agenda. Within the paradigm of performative research, Haseman suggests that this type of undertaking does not necessarily consider a “problem” as in traditional research but is often based on “an enthusiasm of practice” (2006, p. 100). Given the highly subjective nature of both the responses and my own idiosyncratic processing, there is no empirical value in any conclusions I may draw. Rather, I have attempted to present the data in a range of ways so that the trends and tendencies may be explored and interpreted by the reader to whatever depth they desire.

In processing the responses it has become increasingly evident to me that this project exemplifies the performative research methodology in that the interviewees are not sources of data but active participants in a performance of listening that I have had the privilege to document. I illustrate this by offering the edited responses to show both the variety of approaches and the different poetics that are used to express them (with names included should the participant desire). Using McKenna-Buchanan’s method of poetic transcription (2018), we get to hear the “voice” of the participant, rather than just my interpretation. I want to allow the different ways of listening, and articulating listening, to shine in order to illustrate how listening to sound offers both shared commonalities as well as fascinating subjective differences.

What this process has enabled is the development of my own framework—based on my coding classificatons—for closer “reading” of others’ responses as well as a way to assess my own writing about sound. The framework used to analyse the responses can also be applied when listening to compositions and sonic artworks, both those by others and my own, offering a critical language that is based on experience while still implementing a shareable system.

The one conclusion I can stand by is that the listening experience is infinitely rich and varied and affected by peoples’ physiology, histories, tastes, exposure and curiosity. The variation of approaches to listening and levels of engagement with the sounds illustrates the complexity of subject-object relations that occur in listening. By far, the overwhelming response from participants was that they enjoyed the experience of being allowed to listen, and contemplate their listening, for this dedicated period of time. People have different levels of ability to articulate these experiences, but when encouraged to, the experience of listening to their own listening is enlightening for both themselves and myself as documenter.

My reluctance to draw definitive conclusions is due both to the highly subjective nature of listening, and the very nature of writing itself. These interviews attempt to document the process of someone turning their conscious thoughts about listening into speech and then, in its documentation, it becomes text. To unite speech and written text, I draw on Derrida’s notion of arche-writing as the impulse to “languaging”, or Barthes’ notion of écrire, ideas succinctly described by Jean-Luc Nancy as “nothing other than making sense resound beyond signification, or beyond itself” (2007, p. 34). It is the role that language plays in the generative relation between sense as sensation, and sense as meaning, which is the concern of Listening Lingua and the entire Languages of Listening research. Through a focus on the descriptions of sound and listening experiences, my aim was to discover and nurture poetics that don’t translate the untranslatable, but that dwell in the zone that Nancy calls “towards meaning, but ahead of it” (p. 27). I hope that in your encounter with Listening Lingua you experience some of the pleasures that can be found when listening pushes language, and language pushes listening beyond their own senses.

Gail Priest, May, 2022

Notes

(1) Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES) is an experimental introspection testing process developed by Russell T. Hulburt, in which a participant is asked to log their thoughts when randomly prompted by a beeper. Hulburt’s results indicate that people vary greatly as to how much of their thinking takes verbal form. Studies of people in MRI machines indicated that 90% of people experienced inner speech but that it was dominant in only 17%. Based on DES studies outside the MRI testing, Hulburt concludes that 23% of beeped moments involved inner speech (Fernyhough, 2016, Loc 533).

(2) The following graphs indicate the number of instances of each code, divided by the total number of codings within the overall category. For example: number of cause/object responses divided by the total number of modality responses. From this a percentage is derived that allows comparisons to be made within and across codes and classifications.

(3) The sounds referenced in the responses are supplied afterwards. As there are multiple instances there are repetitions, however this allows for easy access and reader choice, which I believe justifies the redundancy.

References

Chion, M. (1983). Guide to sound objects. Pierre Schaeffer and musical research (J. Dack & C. North, Trans.). Éditions Buchet/Chastel. http://ears.pierrecouprie.fr/spip.php?article3597

Cox, C. (2018). Sonic flux: Sound, art and metaphysics . University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (1997). Of grammatology (G. C. Spivak, Trans.; corrected edition). Johns Hopkins University.

Fernyhough, C. (2016). The voices within: The history and science of how we talk to ourselves (E-book). Profile Books/Wellcome Collection.

Grimshaw, M., & Garner, T. (2015). Sonic virtuality: Sound as emergent perception. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199392834.001.0001

Haseman, B. (2006). A manifesto for performative research Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 118, 98–106.

Ihde, D. (2007). Listening and voice: Phenomenologies of sound (2nd ed. E-book.). State University of New York Press.

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. Taylor & Francis.

McKenna-Buchanan, T. (2018). Poetic analysis. In M. Allen (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1–4). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411.n438

Nancy, J.-L. (2007). Listening (C. Mandell, Trans.). Fordham University Press.

Small, C. (1999). Musicking—The meanings of performing and listening. A lecture. Music Education Research, 1(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380990010102

Voegelin, S. (2010). Listening to noise and silence: Towards a philosophy of sound art. Continuum.

Voegelin, S. (2014). Sonic possible worlds: Hearing the continuum of sound. Bloomsbury.

Voegelin, S. (2019). The political possibility of sound: Fragments of listening (E-Book). Bloomsbury Academic.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language (newly revised ed., A. Kozulin, Ed.; E. Hanfmann & G. Vakar, Trans.). MIT Press.